Challenges of mapping the past: Historical railroads

Working with historical maps published during the period encompasses certain risks in terms of precision and accuracy, not to mention bias. During this investigation, this author found sets of maps published from different sources and, possibly, with different agendas in mind.[1] The Department of Interior often published maps that highlighted the evolution of Western Canada. In these maps finished and projected railroad lines were frequently plotted alongside the location of schools, churches and post offices. Similarly, the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) published its own maps reflecting the extension of the rail network or the proposed extension. Land companies that worked in partnership with rail companies regularly distributed maps to potential settlers with information about the state of development in the region where they had land interests. Other sources, mainly booklets and pamphlets aimed at promoting the “West” to potential settlers produced their own maps. While these records are of invaluable importance, they often reflected the “booster” spirit of the times.[2] Frequently, the extension of the railroad network plotted in different maps did not coincide in time and space when compared with similar maps from different sources or with textual records, for instance the reports of the Postmaster General of Canada (RPGC), who described the evolution of the railroad network year by year in his Annual Reports.

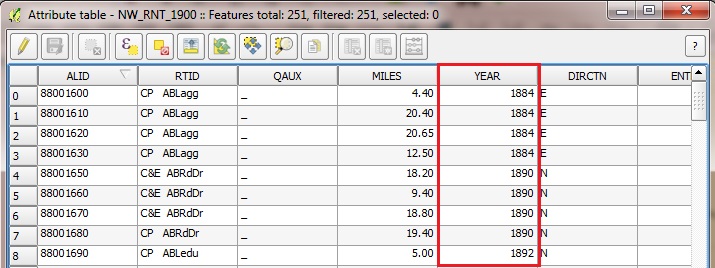

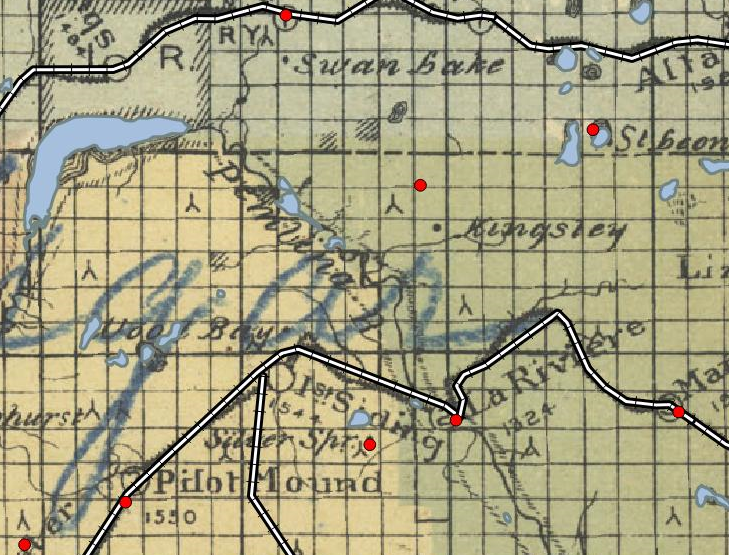

This study considers these disparities. The mapping on GIS of the evolution of the railroad network is based on the actual railroad network of North America.[3] For the purpose of visual simplicity, the GIS study has filtered all the railroads that do not belong to the area. This study then includes only those railroad lines that ran within the old political boundaries established in 1881, in the case of Manitoba, and 1882 when the North-West Territories became three distinct regions: District of Saskatchewan, the District of Assiniboia and the District of Alberta.[4]Similarly, topographic information displayed in maps and representations include only principal rivers within the old boundary. To represent the evolution of the network over time, the database incorporated a “YEAR” column into the GIS project to reflect the year a line extension became operative according to the Report of the Postmaster General (RPGC). [5]

While highly detailed, the layout of maps on GIS confronts technological constraints, mainly coming from the transformation of a nineteenth-century paper map into a geo-referenced digital version. The plot of rail tracks on paper maps was represented with solid, thick lines and did not reflect any scale or proportion. Therefore, the comparison of the railroad lines from paper maps of different visual quality and the digital version of the actual track suffers from certain imprecisions due to scale problems, geo-referencing stretching and coordinate systems.[6] Taking into account these glitches and once compared with maps of the time, the railroad lines overall did not experience substantial changes.

The maps on GIS reflect the evolution of the network year by year as it appeared in the RPGC enhanced with the incorporation of missed information extracted from digitized and geo-referenced maps. In this way, quality control was performed with different sets of data; the one extracted from the textual records and with data from digitized and georeferenced maps. As it happened with other assessment of data quality, visual data and representation are as accurate as possible.

Data

Base GIS shapefiles of Canada and the provinces come from different sources but mainly the dataset of Western Canada townships distribution comes from CCRI and Atlas Canada.[8] Additional data incorporated into GIS tables were extracted from Historical Statistics of Canada and Canada Year Book.[9] Certainly, data collected for this study face some restrictions as they are based on a limited number of published records, mainly due to time constrains; nevertheless, the use is valid as no other source based on post offices and railroad development in Western Canada has been published at the present.

Notes

[1] See the list of maps consulted in the bibliography, http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/3437/

[2] Alan Artibise has explained the “booster” spirit and the idea of selling Winnipeg to potential investors and settlers. See Alan F. J Artibise, “Advertising Winnipeg: The Campaign For Immigrants and Industry, 1874-1914,” MHS Transactions, 3, no. 27 (71 1970), http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/transactions/3/advertisingwinnipeg.shtml and on the Prairies in general, Alan F. J Artibise, “Boosterism and the Development of Prairie Cities, 1871-1913” in R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer, The Prairie West: Historical Readings (University of Alberta, 1992), 515–543; James Belich, Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Angloworld(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 70-72.

[3] Canada. Natural Resources Canada. ‘GeoBase – List of Available Datasets’, accessed 10 March 2014, http://www.geobase.ca/geobase/en/search.do?produit=nrwn&language=en.

[4] Saskatchewan and Alberta became provinces in 1905. Manitoba changed its area in 1881 and obtained its actual size in 1912.

[5] Thomas Thévenin et. al used similar method to reconstruct the French historical railroad. See Thomas Thévenin, Robert Schwartz, and Loïc Sapet, “Mapping the Distortions in Time and Space: The French Railway Network 1830–1930,” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 46, no. 3 (July 1, 2013): 134–43, doi:10.1080/01615440.2013.803409. Also see Richard G. Healey and Trem R. Stamp, “Historical GIS as a Foundation for the Analysis of Regional Economic Growth Theoretical, Methodological, and Practical Issues,” Social Science History 24, no. 3 (September 21, 2000): 593–600, doi:10.1215/01455532-24-3-575.

[6] This is a common problem for every researcher. See for instance Jeremy Atack, “On the Use of Geographic Information Systems in Economic History: The American Transportation Revolution Revisited,” The Journal of Economic History 73, no. 02 (May 23, 2013): 313–38, doi:10.1017/S0022050713000284. A similar issue was raised in William G. Thomas, “Map Inaccuracies in Railroad Sources,” Railroads and the Making of Modern America, 2011, http://railroads.unl.edu/views/item/mapping?p=4.

[7] Excerpt from Bulman Bros. and Co, “Map of Manitoba Published by Authority of the Provincial Government” (Winnipeg: Manitoba Department of Agriculture and Immigration, 1897), University of Manitoba: Archives and Special Collections.

[8] “Census of Canada, Contextual Data, Geography,” Canadian Century Research Infrastructure, accessed September 30, 2012, https://ccri.library.ualberta.ca/enindex.html.

[9] Statistics Canada, ‘Historical Statistics of Canada: Sections’, accessed 10 March 2014, http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-516-x/3000140-eng.htm; Statistics Canada, ‘Canada Year Book (CYB) Historical Collection’, 31 March 2008, http://www65.statcan.gc.ca/acyb_r000-eng.htm.